A Child Born After Death: The Japanese Supreme Court on Posthumous Conception and Legal Parentage

Date of Judgment: September 4, 2006, Supreme Court of Japan (Second Petty Bench)

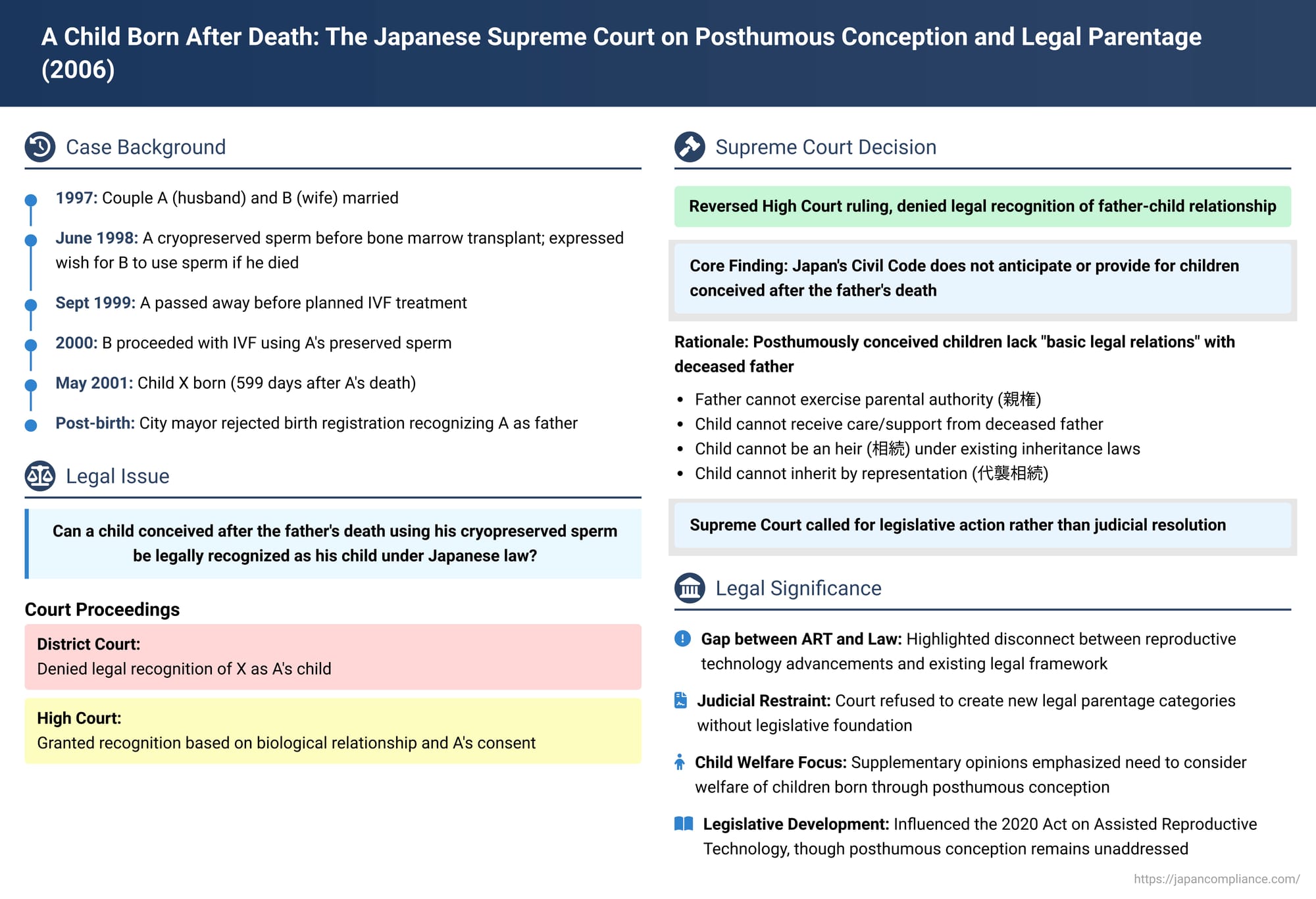

The advancement of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) has opened up new pathways to parenthood, but it has also presented profound legal and ethical challenges that existing laws often struggle to address. One such challenge is posthumous conception—the creation of a child using the cryopreserved sperm of a man after his death. A pivotal Japanese Supreme Court decision on September 4, 2006, grappled with this very issue, determining whether a child conceived and born after the father's death could be legally recognized as his child under Japanese law.

The Facts: A Couple's Hope, A Father's Wish, A Child's Birth

The case involved a couple, A (husband) and B (wife), who married in 1997. A had been undergoing treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia even before their marriage. About six months into their marriage, it was decided that A would undergo a bone marrow transplant. The couple had been pursuing infertility treatment after marrying. Concerned that the extensive radiation therapy associated with the bone marrow transplant would render A infertile (due to azoospermia), they decided to cryopreserve A's sperm at C Hospital in June 1998.

Before undergoing the transplant, A expressed to B his wish that if he were to die and she did not remarry, she should use his preserved sperm to have his child. He also conveyed to his own parents, shortly after his transplant surgery, his desire for B to use his sperm to conceive a child who could continue the family line should anything happen to him. He shared this wish with his brother and aunt as well.

A's bone marrow transplant was successful, and he returned to work. In May 1999, A and B decided to resume their infertility treatment. By late August 1999, they obtained approval from D Hospital to proceed with in vitro fertilization (IVF) using A's cryopreserved sperm. However, before the IVF procedure could take place, A passed away on September 19, 1999.

Following A's death, B, after consulting with A's parents, decided to proceed with IVF using A's preserved sperm. In 2000, she underwent the procedure at D Hospital. On May 10, 2001—599 days after A's death—B gave birth to a child, X, conceived through this process.

B attempted to register X as the legitimate child of both A and B. However, the city mayor rejected this birth registration. Subsequent legal challenges by B against this rejection were unsuccessful.

The Legal Quest for Recognition

Undeterred, B, acting as X's legal representative and custodial parent, filed a lawsuit seeking posthumous legal recognition of X as A's child. In such cases where the father is deceased, the suit is typically filed against a public prosecutor, designated as Y in this matter.

The lower courts arrived at conflicting decisions:

- Trial Court (Matsuyama District Court): Dismissed X's claim for recognition.

- High Court (Takamatsu High Court): Overturned the trial court's decision and granted recognition. The High Court reasoned that in cases of artificial insemination, the existence of a biological blood relationship between the child and the father, coupled with the father's consent to the conception, were necessary and sufficient conditions for recognition, provided there were no special circumstances making recognition inappropriate. The High Court found that these conditions were met in X's case, particularly noting A's expressed wishes.

Prosecutor Y appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Judgment (September 4, 2006)

In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court overturned the High Court's ruling and dismissed X's claim for recognition, thereby siding with the trial court's initial judgment.

Core Rationale: Existing Law Does Not Envision Posthumous Conception

The Supreme Court's central reasoning was that Japan's Civil Code, in its provisions concerning parent-child relationships, simply does not anticipate or provide for children conceived after the death of the genetic father.

The Court elaborated on several key legal aspects that would normally define a parent-child relationship, none of which could apply to a posthumously conceived child and their deceased father under the current legal framework:

- Parental Authority (親権 - shinken): A father who is deceased at the time of the child's conception and birth cannot exercise parental authority over the child.

- Support and Upbringing (監護, 養育, 扶養 - kango, yōiku, fuyō): The child cannot receive care, upbringing, or financial support directly from the deceased father.

- Inheritance (相続 - sōzoku): A posthumously conceived child cannot be considered an heir to the deceased father under existing inheritance laws. The Court reasoned that for inheritance to occur, the child must exist (at least en ventre sa mère, conceived) at the time of the father's death.

- Succession by Representation (代襲相続 - daishū sōzoku): Similarly, because the posthumously conceived child cannot inherit from the deceased father directly, they also cannot become an heir by representation (i.e., inheriting in place of their deceased father from, for example, their grandparents). This is because the right to representational inheritance is generally predicated on the representative (the child) being in a position to inherit from the person they are representing (the deceased father).

The Supreme Court concluded that the relationship between a posthumously conceived child and the deceased genetic father fundamentally lacks the "basic legal relations" that the Civil Code establishes for parent-child relationships.

The Call for Legislative Action

Crucially, the Supreme Court stated that the question of whether to establish legal parentage for posthumously conceived children is a matter that must be resolved through legislative action. Such legislation would need to be preceded by comprehensive and multifaceted debate, considering:

- Bioethical implications of using a deceased person's gametes.

- The welfare of the child born through such means.

- The perspectives and interests of all parties involved, including the surviving parent, the deceased's family, and society at large.

- General societal consensus on these complex issues.

In the absence of such specific legislation addressing the requirements and effects of recognizing parentage for posthumously conceived children, the Court found that such legal parent-child relationships could not be acknowledged.

Supplementary Opinions: Focus on Child Welfare and Legislative Urgency

Two of the justices issued supplementary opinions. While concurring with the majority's conclusion to deny recognition under the current law, they both underscored the paramount importance of considering the "welfare of the born child." They also strongly urged the legislature to undertake "prompt" or "early" legal reforms to address the novel legal issues arising from advancements in assisted reproductive technology.

The Broader Legal and Ethical Context in Japan

The Supreme Court's decision was delivered against a backdrop of evolving medical practices and existing, though not always legally binding, ethical guidelines.

- Current Civil Code and ART: The Japanese Civil Code's provisions on parentage were primarily designed around natural conception. For instance, the presumption of legitimacy (Article 772), which presumes a child born within 300 days of the dissolution of a marriage to have been conceived during that marriage, was clearly inapplicable to X, who was born 599 days after A's death. The legal mechanism of "recognition" (ninchi), typically used to establish paternity for children born outside of marriage, also presupposed scenarios distinct from posthumous conception.

- Prevailing Medical Ethics and Guidelines: At the time of A's sperm cryopreservation and X's conception, there were developing views within the medical and regulatory community regarding the posthumous use of gametes.

- The High Court's fact-finding, as detailed in legal commentaries, indicated that C Hospital, where A's sperm was stored, had a policy (which A and B acknowledged in writing) stating that preserved sperm belonged to the donor, storage was limited to the donor's lifetime, the sperm would be discarded upon the donor's death, and it would not be used for posthumous assisted reproduction.

- A 2003 report by a specialized committee of the Health Science Council (an advisory body to the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare) recommended that donated sperm, ova, or embryos should be discarded upon confirmation of the donor's death.

- The Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG), in a 2007 "View on Cryopreservation of Sperm," stated that at the time of using cryopreserved sperm, the donor's survival and intention should be confirmed, and that sperm should be discarded if the donor expresses a wish for its disposal or in the event of the donor's death.

These guidelines, while not necessarily having the force of law binding on the courts in a parentage dispute, reflected a cautious or prohibitive stance in the medical and ethical discourse surrounding posthumous reproduction.

- The Deceased's Consent: While A had clearly expressed his wish for a child to be born after his death using his sperm, and the High Court had considered this a crucial factor, the Supreme Court's decision indicates that under the existing legal framework, even such consent cannot create legal parentage where the law itself does not provide for it. The situation also raises broader ethical questions about the nature of consent to create a life that will intentionally be fatherless from conception, and the balance between respecting the deceased's wishes and considering the future child's welfare.

- Distinctions in ART Scenarios: Legal commentators have noted the importance of distinguishing between various ART scenarios. For instance, the legal and ethical considerations for posthumous insemination (using cryopreserved sperm after the man's death, as in this case) might differ from those for posthumous embryo transfer (transferring an embryo that was created and cryopreserved before the man's or woman's death). This case specifically dealt with posthumous insemination.

Legislative Developments (Post-Judgment)

The Supreme Court's call for legislative action has been a recurring theme in cases involving ART.

- In 2020, Japan enacted the "Act on Special Provisions to the Civil Code Concerning Parent-Child Relationships with Regard to Assisted Reproductive Technology Provided by a Third Party and Other Related Matters" (Act on Assisted Reproductive Technology, Law No. 76 of Reiwa 2). This law primarily addresses issues like defining legal parentage in cases of third-party gamete donation.

- Crucially, this 2020 Act does not currently include provisions specifically addressing posthumous conception. However, its Supplementary Article 3 mandates that the government shall review the status of ART and related matters within approximately two years of the Act's enforcement and take necessary legislative or other measures based on the results of that review.

- It has been suggested by some involved in the legislative process that this review clause does not preclude future consideration of posthumous conception, indicating that the issue remains on the legislative agenda.

- Discussions regarding broader reforms to Japan's parent-child law within the Civil Code, taking into account ART advancements, are also ongoing within bodies like the Legislative Council of the Ministry of Justice.

Conclusion

The Japanese Supreme Court's 2006 decision in the case of X, the child conceived after the death of her genetic father A, firmly established that, under the then-existing legal framework, legal parentage could not be recognized in such circumstances. The Court made it clear that while it understood the emotional and personal desires involved, the creation of legal parent-child relationships in these novel scenarios falls within the purview of the legislature, requiring careful and comprehensive societal debate.

The judgment highlighted the significant gap between the capabilities of modern reproductive medicine and the provisions of a legal system largely designed around natural conception. It underscored that fundamental legal relationships, such as those involving parental rights, support obligations, and inheritance, could not be automatically extended to posthumously conceived children without explicit legislative intervention. While the supplementary opinions voiced strong support for prioritizing the welfare of children already born through such means and urged swift legislative action, the core decision emphasized that courts could not create new categories of legal parentage where the law itself was silent or did not provide a basis. The case remains a critical reference point in discussions about the legal and ethical governance of assisted reproductive technologies in Japan and the ongoing quest to adapt legal frameworks to the realities of scientific progress.