A Change of Heart, A Question of Blood: Can You Undo Your Own Paternity Acknowledgment in Japan?

Judgment Date: January 14, 2014 (Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench)

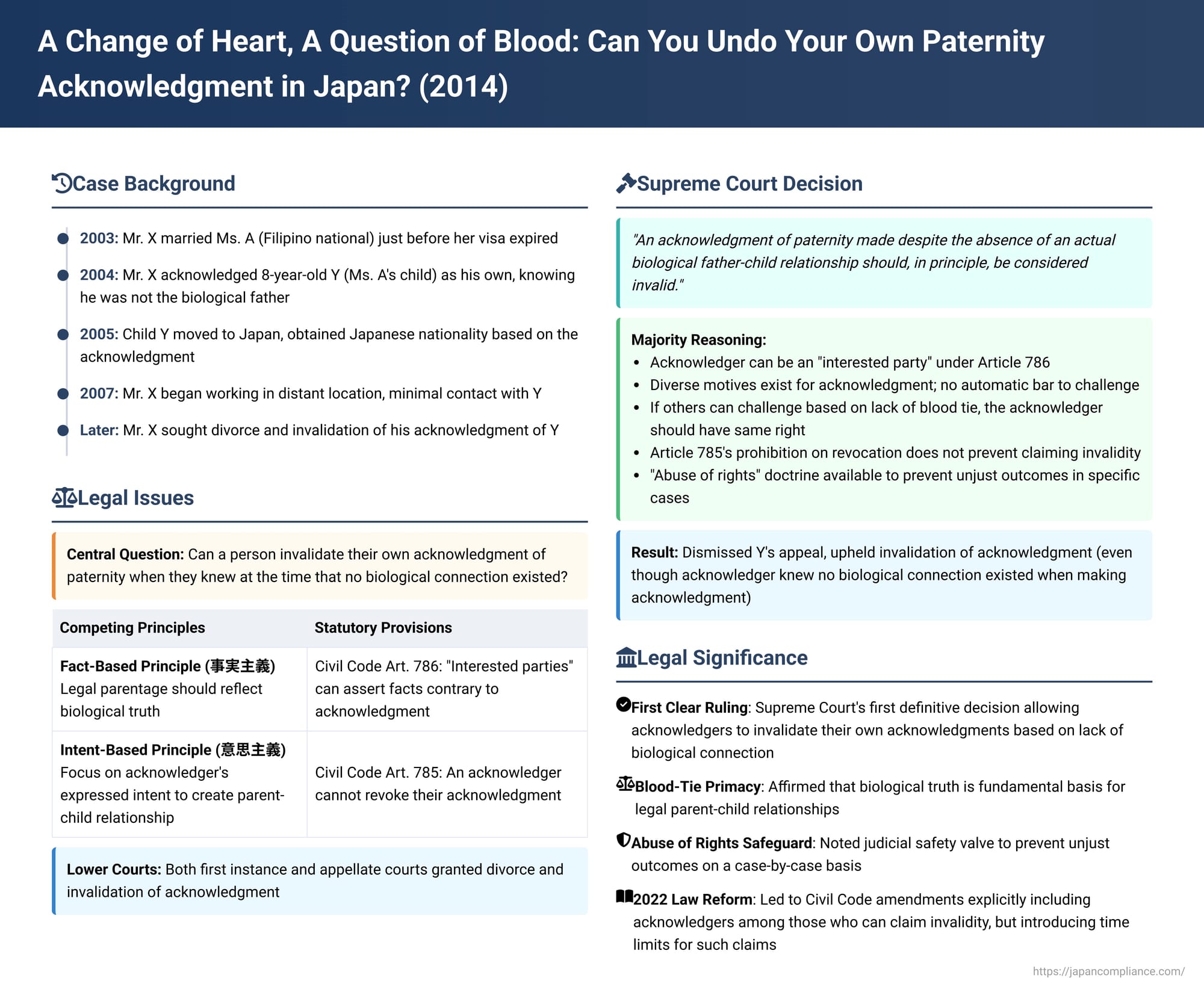

In a significant 2014 decision, Japan's Supreme Court tackled a contentious issue at the heart of family law: can a person who acknowledged paternity of a child, knowing at the time that there was no biological connection, later seek to invalidate that very acknowledgment? The Court said yes, a decision that affirmed the primacy of biological truth in establishing legal parentage but also hinted at safeguards to prevent undue hardship, a stance largely codified and nuanced by subsequent legal reforms.

The Facts: A Marriage, A Child from Abroad, and a Fraying Bond

The case involved Mr. X, who married Ms. A, a Filipina national, in 2003. The marriage took place shortly before Ms. A's visa for Japan was due to expire. After their marriage, Ms. A revealed to Mr. X that she had children in the Philippines and expressed a desire to bring one of them, her youngest child Y, to Japan.

In 2004, Mr. X formally acknowledged Y, then eight years old, as his own child. Crucially, Mr. X was aware at the time of this acknowledgment that he was not Y's biological father. Ms. A had two other children in the Philippines, but Mr. X declined to acknowledge them.

In 2005, Y arrived in Japan and began living with Mr. X and Ms. A in Hiroshima Prefecture. By December of that year, Y had successfully obtained Japanese nationality, a process facilitated by Mr. X's acknowledgment (under the provisions of Japan's Nationality Act, Article 3, as it stood before a 2008 revision).

For nearly five years, Y lived in Japan and was reportedly adapting to the new environment. However, the relationship between Y and Mr. X was consistently strained. In 2007, Mr. X began working in a distant location (Toyama Prefecture), leading to him and Y living separately. Thereafter, contact between them became minimal.

Eventually, Mr. X initiated legal proceedings, seeking a divorce from Ms. A and, critically for this Supreme Court case, a declaration that his acknowledgment of Y was legally invalid.

The Legal Path: Lower Courts Agree with Invalidation

Both the court of first instance and the appellate court sided with Mr. X, granting the divorce and affirming the invalidity of his acknowledgment of Y. Y then sought to appeal to the Supreme Court, but the Court accepted the appeal only on the issue of the acknowledgment's invalidity.

The Supreme Court's Verdict: Acknowledger Can Challenge His Own Act

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' decisions that Mr. X's acknowledgment was invalid. The majority reasoned:

- Absence of Blood Tie is Key: An acknowledgment of paternity made despite the absence of an actual biological father-child relationship should, in principle, be considered invalid.

- Acknowledger's Varied Motives: People acknowledge children for diverse reasons. It would be inappropriate to create an absolute rule preventing an acknowledger from ever challenging their own acknowledgment simply because they made it voluntarily.

- Consistency with Rights of Other Interested Parties: Japan's Civil Code (Article 786) already allows other "interested parties" (e.g., the child, the mother, other heirs) to challenge an acknowledgment if there's no biological link. If these parties can assert invalidity, there is little compelling reason, even considering the child's protection, to uniformly bar the acknowledger himself from doing so.

- Abuse of Rights as a Safeguard: If, in a specific case, allowing the acknowledger to assert invalidity would be unjust or harmful, the doctrine of "abuse of rights" can be invoked to restrict such a claim. This provides a case-by-case mechanism to prevent unfair outcomes.

- Acknowledger's Strong Interest: The person who made the acknowledgment clearly has a significant personal interest in its legal validity.

- Article 785 Not a Bar: Civil Code Article 785, which prohibits an acknowledger from revoking their acknowledgment, should not be interpreted as preventing them from asserting its invalidity based on a lack of biological connection. (Revocation implies undoing a valid act, while asserting invalidity means arguing the act was void from the start).

- Acknowledger as an "Interested Party": Therefore, the acknowledger qualifies as an "interested party" under Article 786 and can assert the invalidity of their own acknowledgment. This holds true even if, as in Mr. X's situation, the acknowledger knew of the absence of a biological tie when making the acknowledgment.

The decision was not unanimous. There was a concurring supplementary opinion from Justice Kiuchi, a concurring opinion (agreeing with the outcome but on different grounds for this specific case) from Justice Terada, and a dissenting opinion from Justice Ohashi, who argued against allowing the acknowledger to claim invalidity.

Landmark Ruling and Subsequent Legal Changes

This 2014 judgment was significant as it was the Supreme Court's first clear ruling on whether an acknowledger could seek to invalidate their own acknowledgment based on a lack of biological ties. It endorsed the "affirmative view"—that the acknowledger indeed has this right. This stance was echoed by another Supreme Court (Second Petty Bench) decision shortly thereafter on March 28, 2014.

The legal landscape has since evolved further. In 2022 (Reiwa 4), the Japanese Diet passed Law No. 102, amending the Civil Code. These amendments specifically address who can assert the invalidity of an acknowledgment and, importantly, introduce time limits for doing so. The revised law explicitly includes the acknowledger among those who can claim invalidity. This legislative change effectively codifies the Supreme Court's 2014 decision in this regard.

The Doctrinal Bedrock: Biological Truth vs. Declared Intent

The question of who can challenge an acknowledgment, and on what grounds, touches upon a fundamental debate in Japanese family law regarding the nature of acknowledgment itself. The Civil Code provides limited guidance on what makes an acknowledgment invalid or subject to revocation, merely stating that an acknowledger cannot revoke it (Art. 785) and that interested parties can assert "contrary facts" (Art. 786).

To fill this interpretive gap, legal scholarship has explored two main approaches:

- Fact-Based (Blood-Tie) Principle (事実主義, jijitsu-shugi): This view posits that legal parent-child relationships, including those established by acknowledgment, are fundamentally based on biological blood ties. This principle readily explains:

- Compulsory acknowledgment (Art. 787), where a court can order acknowledgment if a blood tie is proven.

- The "contrary facts" in Art. 786, which are understood to mean the absence of a blood tie, rendering the acknowledgment invalid.

- Within this framework, a voluntary acknowledgment is often seen as an admission by the acknowledger of an existing blood relationship, creating a presumption of paternity similar to how marriage creates a presumption regarding children born to the wife (Art. 772). Article 785 (no revocation) is then interpreted as preventing the withdrawal of this admission. Some proponents of this view argue that if a blood tie truly exists, even an acknowledgment made due to fraud or duress cannot be undone; the validity hinges solely on biology. Allowing the acknowledger (like Mr. X) to later assert the absence of a blood tie aligns with this emphasis on biological reality.

- Intent-Based Principle (意思主義, ishi-shugi): This approach places greater emphasis on the acknowledger's expressed will and intent to create a parent-child relationship.

The 2014 Supreme Court ruling, and the subsequent 2022 Civil Code amendments, fundamentally ground the invalidity of an acknowledgment in the fact-based, blood-tie principle.

Policy Arguments and the Child's Welfare

Prior to the 2014 ruling and the 2022 legal reforms, a "recent negative view" was gaining traction, arguing against allowing the acknowledger to challenge their own act. This perspective emphasized that the acknowledgment system serves purposes beyond simply reflecting biological truth, particularly given that DNA technology can now readily ascertain biological connections. Proponents of this view highlighted several policy considerations:

- Protection of the Child and Mother: Ensuring a legal guardian for the child through the early finalization and stabilization of the parent-child relationship.

- Historical Context: The acknowledgment system was also seen, historically, as a way to support mothers in difficult situations, potentially even preventing infanticide by providing a path to legal parentage and support.

- Analogies to De Facto Adoptions: Parallels were drawn to situations where false registrations of legitimate birth were, under certain circumstances, upheld if a genuine social parent-child relationship had formed and was reflected in public records like the family register.

This view sought to relativize the "biological truth" requirement by injecting these broader policy goals.

The 2022 Civil Code amendments, while codifying the acknowledger's right to challenge based on lack of a blood tie (in line with the 2014 ruling), also incorporated a significant element that addresses these stability concerns: time limits for asserting such invalidity (new Art. 786(1) main text). This introduction of statutory limitation periods can be seen as a nod to the arguments for early finalization and stability of the child's status. However, these time limits currently apply only to claims of invalidity based on the absence of a blood tie under Article 786, not necessarily to other potential grounds for an acknowledgment being void (e.g., lack of capacity).

The Role of "Abuse of Rights" as a Judicial Safeguard

A crucial element of the Supreme Court's 2014 majority opinion was its explicit mention that an acknowledger's assertion of invalidity could, in specific circumstances, be restricted by the doctrine of "abuse of rights" (権利濫用, kenri ranyō). This legal principle allows courts to prevent a party from exercising a right in a way that, while technically permissible, is unconscionable or causes undue harm to another party, violating fundamental principles of good faith and social justice.

The Supreme Court has previously employed the abuse of rights doctrine in other family law contexts, for example, to prevent the denial of parentage in cases involving false registrations of legitimate birth where a stable parent-child relationship has existed for a long time, prioritizing the established relationship over the biological truth. It's conceivable that even if an acknowledgment lacks a biological basis (which, under a 1975 Supreme Court precedent, would render it invalid), a court might still prevent its invalidation if doing so would constitute an abuse of rights—for instance, if the acknowledger sought invalidation after many years during which the child relied on the acknowledged status. This doctrine serves as a potential judicial safety valve against purely opportunistic or excessively harsh outcomes.

Ulterior Motives: Acknowledgment for Nationality and "Sham" Acts

The specific facts of Mr. X and Y's case also brought another layer of complexity: the acknowledgment appeared to be, at least in part, motivated by a desire to enable Y to immigrate to Japan and obtain Japanese nationality. This raises questions about acknowledgments made for such "instrumental" or "convenience" purposes.

The 2022 legal reforms directly addressed the issue of fraudulent acknowledgments aimed at nationality acquisition:

- While criminal penalties for false declarations related to the family register (Penal Code Art. 157) and fraudulent nationality acquisition (Nationality Act Art. 20) already existed, the Nationality Act was amended (new Art. 3(3)).

- This new provision stipulates that, notwithstanding the new time limits for challenging the validity of an acknowledgment under the Civil Code, Japanese nationality cannot be acquired under Article 3 of the Nationality Act (which deals with acquisition by acknowledgment) if the acknowledgment is, in fact, contrary to biological reality (i.e., no blood tie exists).

This amendment effectively decouples the private law validity of an acknowledgment (which might become unchallengeable after a certain period) from its efficacy for nationality acquisition (which always requires a true biological link).

However, beyond nationality, if an acknowledgment is primarily a "sham status act" (仮装身分行為, kasō mibun kōi)—a legal fiction entered into for purposes entirely unrelated to forming a genuine parent-child relationship—its validity under private law itself could still be questioned under Article 90 of the Civil Code, which voids acts contrary to public order and morality. Whether such a challenge would be subject to time limits or abuse of rights arguments is a matter for future legal interpretation. Interestingly, some of the recent arguments against allowing an acknowledger to challenge their act might view even these "convenience acknowledgments" as legitimate uses of the system if the underlying intent is to raise the child as one's own, effectively creating a de facto familial bond.

Conclusion: A Path Forward Balancing Truth, Intent, and Stability

The 2014 Supreme Court decision allowing an acknowledger to seek invalidation of their own non-biological acknowledgment marked a significant clarification in Japanese family law, strongly affirming the principle that legal paternity should, at its core, reflect biological truth. The subsequent 2022 Civil Code amendments have built upon this, codifying the acknowledger's right to challenge while also introducing time limits, thereby attempting to strike a balance between correcting factually inaccurate acknowledgments and ensuring a degree of stability for the child's legal status.

The interplay of these rules with the doctrine of abuse of rights, and the separate considerations for acknowledgments motivated by extraneous factors like nationality acquisition, demonstrates the ongoing effort within Japanese law to navigate the complex triangle of biological reality, declared parental intent, the welfare of the child, and broader public policy concerns. While the door is open for acknowledgers to correct the record, it is not without potential checks and balances designed to prevent injustice.