A Century-Old Rule Challenged: Japan's Supreme Court on Women's Remarriage Ban and Paternity Presumptions

Date of Judgment: December 16, 2015

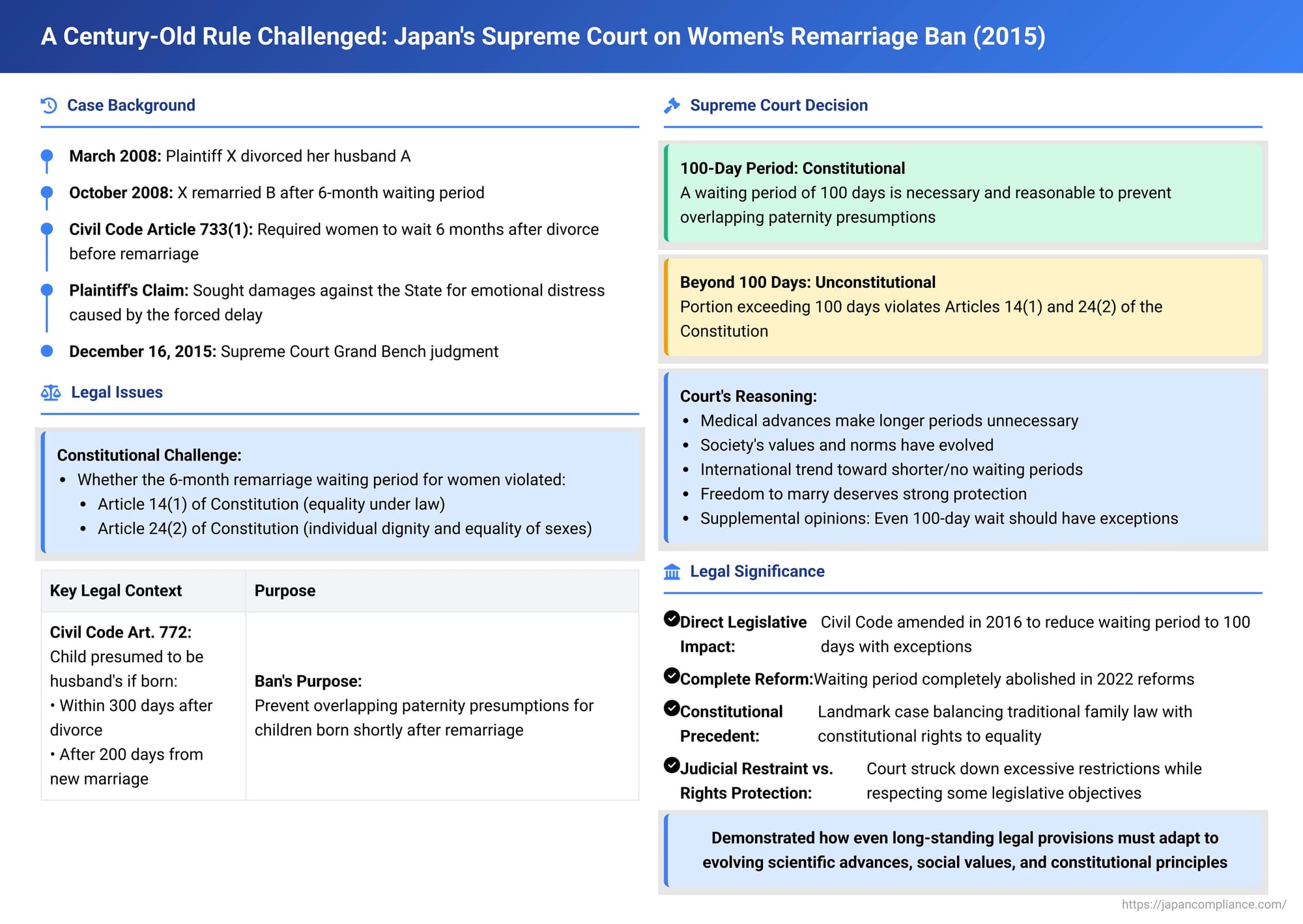

For over a century, Japanese law included a provision that uniquely affected women: a mandated waiting period after the dissolution of a marriage before they could remarry. This rule, enshrined in Article 733, paragraph 1 of the Civil Code, stipulated a six-month (180-day) interval. Proponents argued it was necessary to prevent uncertainty regarding the paternity of children born shortly after remarriage. Critics, however, contended it was an anachronistic and discriminatory measure, infringing upon women's freedom of marriage and violating constitutional principles of equality. This long-standing debate reached a critical juncture in a landmark decision by the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on December 16, 2015 (Heisei 25 (O) No. 1079).

The Plaintiff's Ordeal and the Constitutional Challenge

The case was brought by X, a woman whose personal life was directly impacted by this law. X divorced her former husband, A, on a day in March 2008. She wished to remarry her new partner, B, but due to the then-existing six-month waiting period mandated by Civil Code Article 733(1) (referred to as "the provision"), her remarriage to B was delayed until October 2008. X claimed that this forced delay caused her emotional distress.

Her lawsuit was not directly against the provision itself but was a claim for damages against the State (Y) under the State Compensation Law. X argued that the National Diet (Japan's legislature) had acted illegally by failing to amend or abolish Article 733(1), which she contended was unconstitutional. Specifically, she asserted that the provision violated Article 14, paragraph 1 of the Constitution of Japan (guaranteeing equality under the law and prohibiting discrimination based on sex) and Article 24, paragraph 2 (which mandates that laws pertaining to marriage and the family shall be enacted from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes).

The lower courts (Okayama District Court and Hiroshima High Court, Okayama Branch) had dismissed X's claim. While the High Court acknowledged the legislative purpose of the provision as reasonable, it did not directly rule on its constitutionality before dismissing the compensation claim. X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Constitutional Adjudication

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court, while ultimately dismissing X's claim for monetary damages due to legislative inaction, delivered a groundbreaking judgment on the constitutionality of the remarriage waiting period for women.

1. The Stated Legislative Purpose: Avoiding Paternity Confusion

The Court began by affirming the commonly understood legislative purpose of Article 733(1): "The legislative purpose of the provision is reasonably understood to be the avoidance of overlapping presumptions of paternity for a child born after a woman's remarriage, thereby preventing disputes concerning paternity." The Court referenced a 1995 Supreme Court decision and emphasized that ensuring the early clarification of a child's paternity is an important objective, making this legislative aim reasonable in itself.

This purpose is intrinsically linked to Japan's system of presuming legitimacy (嫡出推定 - chakushutsu suitei) under Civil Code Article 772. This article stipulates that:

- A child conceived by a wife during marriage is presumed to be the child of the husband (Art. 772(1)).

- A child born 200 days or more after the formation of a marriage, or within 300 days of the dissolution or annulment of a marriage, is presumed to have been conceived during that marriage (Art. 772(2)).

If a woman remarries very soon after her previous marriage ends and then gives birth, it's possible for the child to fall within the 300-day presumption period of the first husband and the 200-day presumption period of the second husband, creating conflicting legal presumptions about paternity. The remarriage waiting period was intended to prevent such direct overlaps.

2. A Partial Unconstitutionality Finding: The 100-Day Divide

The Supreme Court then made a crucial distinction:

- A 100-Day Waiting Period Deemed Constitutional: The Court calculated that a waiting period of 100 days is sufficient to prevent the direct overlap of paternity presumptions based on the timeframes in Article 772 (300 days for the former marriage minus 200 days for the subsequent marriage leaves a 100-day window where a child born could be presumed to belong to either). The Court held that imposing such a 100-day restriction on women's remarriage to ensure the legal stability of a child's status through clear and uniform criteria (marriage status and birth timing) is within the bounds of rational legislative discretion and does not violate Article 14(1) or Article 24(2) of the Constitution. This part of the provision was considered a reasonable means to achieve its legitimate legislative purpose.

- The Portion Exceeding 100 Days Deemed Unconstitutional: However, the Supreme Court ruled that the part of Article 733(1) that imposed a remarriage waiting period beyond these 100 days was an excessive restriction and therefore unconstitutional.

3. Reasons for Finding the >100 Day Portion Unconstitutional:

The Court provided several reasons for striking down the excess period:

- Advances in Medical and Scientific Technology: The original Meiji-era justifications for a longer period (the old Civil Code also had a six-month ban) included difficulties in accurately determining pregnancy in its early stages and a lack of reliable paternity testing. These concerns also encompassed preventing "confusion of bloodlines" or family discord if a child from a previous husband was born into a new marriage. The Court found that in modern times, with advanced medical technology for pregnancy detection and DNA testing for paternity, these historical rationales for a period longer than what is strictly necessary to avoid overlapping presumptions had become difficult to sustain.

- Changing Social Norms and the Importance of Marital Freedom: The Court acknowledged significant societal shifts, including an increase in divorce and remarriage rates, and a growing societal demand to minimize restrictions on the freedom to remarry. It also noted the international trend of many countries shortening or abolishing similar waiting periods for women. The freedom to marry, including when and whom to marry, is a value deserving of full respect under the Constitution (specifically Article 24, paragraph 1, which guarantees freedom of marriage based on mutual consent and equality of the sexes).

- Excessive and Irrational Restriction: Given these advancements and societal changes, imposing a waiting period longer than the 100 days scientifically calculated to prevent overlapping paternity presumptions was deemed an excessive and irrational restriction on women's freedom of marriage. The Court also pointed out that issues related to children conceived before marriage are not exclusive to remarriage scenarios. Therefore, specifically targeting remarried women with a ban longer than 100 days lacked a compelling justification.

- Conclusion on Constitutionality: The Court concluded that, by around 2008 (the time of X's divorce and remarriage), the portion of Article 733(1) mandating a remarriage prohibition period beyond 100 days had become unconstitutional, violating both Article 14, paragraph 1 (equality under the law) and Article 24, paragraph 2 (individual dignity and essential equality of the sexes in family law) of the Constitution.

4. Legislative Inaction and State Compensation: No Damages Awarded

Despite finding a part of the law unconstitutional, the Supreme Court did not award damages to X. The Court maintains a very high bar for holding the Diet liable for "legislative inaction" under the State Compensation Law. It generally requires that the unconstitutionality of a law (or the necessity of enacting one) be "clear" to Parliament, and that Parliament has failed to act for an unreasonably long period without just cause.

In this instance, the Court reasoned that a 1995 Supreme Court decision had addressed the remarriage waiting period but had not found it unconstitutional (it dismissed a similar compensation claim on other grounds). This earlier ruling, the 2015 Court suggested, might have led legislators to believe that the existing provision was within their discretionary powers. Furthermore, although reform proposals, including one to shorten the period to 100 days, had been discussed (e.g., a 1996 proposal by the Legislative Council), these were not explicitly framed around the unconstitutionality of the excess period. Therefore, the Court concluded that it was not "clear" to the Diet that the portion of the law exceeding 100 days was unconstitutional, and thus their failure to amend it earlier did not constitute an illegal act for state compensation purposes.

5. Supplemental Opinions and Potential Exceptions to the 100-Day Rule

The judgment was accompanied by several supplemental and dissenting opinions. Notably, a joint supplemental opinion by six justices (with two others concurring on this point) explored the possibility of recognizing exceptions even to the 100-day waiting period that the majority found constitutional. They argued that if the legislative purpose is purely to avoid overlapping paternity presumptions, then the 100-day ban should not apply in situations where such an overlap is impossible.

Examples suggested included:

- Cases where the woman is biologically incapable of conceiving (e.g., due to sterilization or age).

- Cases where the woman can provide medical certification that she was not pregnant at the time of the dissolution of her previous marriage.

This line of reasoning in the supplemental opinion acknowledged that a strict, unexcepted 100-day ban could still impose unnecessary hardship in clear-cut cases. One justice in this group even opined that without such exceptions, the 100-day rule itself would be unconstitutional.

Aftermath: Legislative Reform Prompted by the Ruling

This landmark Supreme Court decision had a direct and significant impact on the law. Following the ruling:

- In 2016, the Japanese Civil Code was amended (Law No. 71 of 2016). Article 733 was revised to shorten the remarriage waiting period for women from six months to 100 days. Crucially, the amendment also incorporated exceptions similar to those discussed in the supplemental opinion: the 100-day waiting period does not apply if a woman provides a medical certificate stating she was not pregnant at the time of the dissolution of her previous marriage, or if she is remarrying her former husband, among other specific circumstances.

- More recently, further reforms to Japan's parentage laws led to the complete abolition of the 100-day remarriage prohibition period for women (Law No. 102 of Reiwa 4/2022, effective from April 1, 2024). This was part of a broader overhaul of the rules concerning presumption of legitimacy, aiming to better reflect modern family realities and scientific capabilities.

Conclusion: A Catalyst for Change in Family Law

The Supreme Court's 2015 decision on the women's remarriage waiting period was a pivotal moment in Japanese constitutional and family law. By declaring the portion of the then-existing six-month ban exceeding 100 days unconstitutional, the Court sent a strong message about the importance of gender equality and the freedom of marriage. While it stopped short of awarding damages for past legislative inaction, the ruling directly catalyzed legislative reform, first leading to a significant reduction and qualification of the waiting period in 2016, and ultimately contributing to its complete abolition in 2022.

The judgment carefully balanced the acknowledged legislative aim of preventing paternity confusion with the fundamental rights of individuals, demonstrating that even long-standing legal provisions must adapt to evolving societal values, scientific advancements, and constitutional principles. It stands as a testament to the dynamic interplay between the judiciary and the legislature in shaping a legal framework that is both rational and just.