A Case of Mistaken Identity: Japan's Supreme Court on Patient Identification Failures in Team Medicine

Date of Decision: March 26, 2007, Supreme Court of Japan (Second Petty Bench)

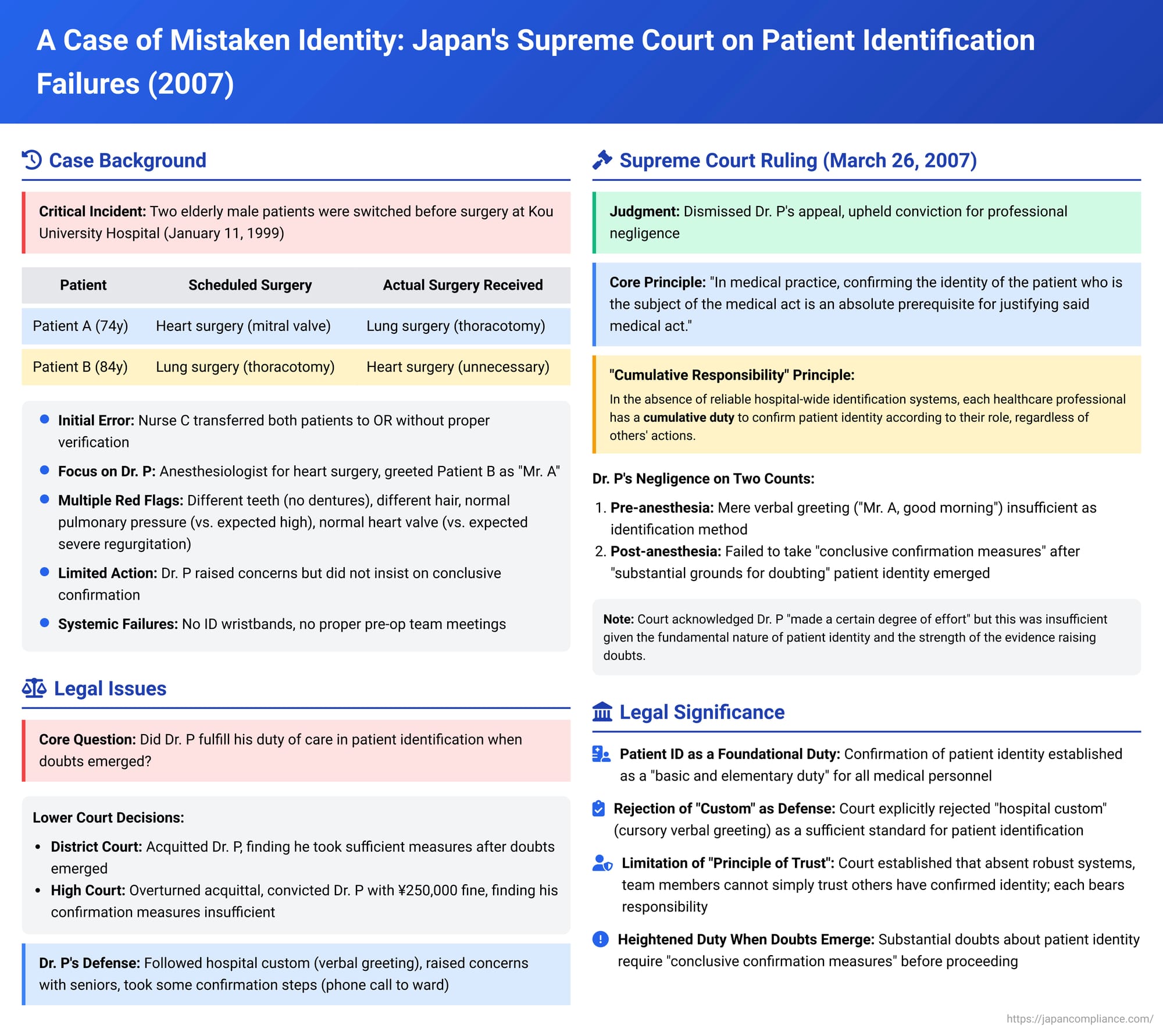

Few errors in medicine are as profoundly devastating and fundamentally preventable as patient mix-ups leading to wrong-site or wrong-patient surgery. Such incidents strike at the core of patient trust and safety. A landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on March 26, 2007, scrutinized a catastrophic patient swap incident, offering critical legal perspectives on the responsibilities of individual medical team members, particularly when systemic safeguards for patient identification are deficient.

The Incident: Two Patients, Two Surgeries, One Critical Mix-Up

The case unfolded at Kou University Hospital on January 11, 1999. Two elderly male patients were scheduled for simultaneous, major surgeries at 9:00 AM:

- Patient A: 74 years old, scheduled for heart surgery (mitral valve repair or replacement).

- Patient B: 84 years old, scheduled for lung surgery (exploratory thoracotomy for suspected lung cancer).

The two men were described as having considerably different physical appearances, including their facial features and hairstyles.

The chain of errors began during the patient handover process. Nurse C, a ward nurse, single-handedly transferred both Patient A and Patient B on stretchers from their ward to the operating room exchange D. Nurse C did not hand over each patient simultaneously with their respective medical charts, and the verbal confirmation of their names with Nurse D, an operating room nurse, was ambiguous. This resulted in Nurse D mistakenly identifying Patient A as Patient B, and Patient B as Patient A, and subsequently handing them over to the incorrect surgical teams.

The focus of the Supreme Court appeal was on Dr. P, the primary anesthesiologist assigned to Patient A's heart surgery.

Around 8:40 AM, Dr. P entered the operating room where Patient B (mistaken for Patient A) lay on the operating table. Dr. P greeted the patient, "Mr. A, good morning," and asked questions like, "Mr. A, which hand do you use to eat? Your right hand, correct?" Patient B nodded in response to these greetings. Dr. P, without further conscious effort to confirm the patient's identity through physical features or more specific questioning, proceeded with the anesthesia, assisted by a second anesthesiologist, Dr. S.

Doubts Emerge:

As Dr. P was intubating the patient, he noticed discrepancies. Dr. P recalled from his pre-operative consultation with Patient A that Patient A had upper dentures which were to be removed before surgery. However, the patient on the table had a full set of teeth. Dr. P tugged at the teeth and consulted a nurse but could not ascertain the reason for this discrepancy and did not pursue it further at that moment. He also did not pay attention to any heart murmur or chest hair during auscultation. Later, when a hair cap on the patient shifted, Dr. P noticed the patient’s hair was sparse and white, whereas he remembered Patient A's hair being relatively dark and full for his age. He questioned Dr. S about this, but Dr. S did not provide a clear answer.

More significantly, when Dr. P measured the patient's pulmonary artery pressure, it was normal (around 13 mmHg). This was surprising, as Patient A's pre-operative tests had shown significantly elevated pulmonary artery pressure (mean 42 mmHg) due to severe mitral regurgitation. Dr. P questioned Dr. S if anesthesia could cause such a drop or if the patient's condition had improved; Dr. S did not deny these possibilities. Furthermore, a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) performed in the operating room showed no mitral valve prolapse or ruptured chordae tendineae, and only minimal blood regurgitation—a stark contrast to Patient A's known severe 4-degree regurgitation which necessitated the surgery. The TEE findings indicated an essentially normal heart for an elderly person, not requiring surgery.

By this time, attending physicians for Patient A's surgery, Dr. E1 and Dr. E2, were present. They discussed the TEE results, suggesting the lowered pulmonary artery pressure might have reduced the regurgitation or that anesthesia might be the cause. Dr. P, now with accumulating doubts due to the discrepancies in dentures, hair, and the dramatic differences in test results, voiced his concern to Dr. S, Dr. E1, and Dr. E2, stating that the patient’s hair looked different and asking if they were sure it was Patient A. Dr. E2 reportedly commented, "Maybe he got a haircut?"

Dr. P then asked Dr. S to have the attending physicians re-examine the patient thoroughly. He also recalled seeing a notice about another patient with a similar name and had an assisting nurse call the ward. The ward nurse confirmed that "Patient A" had indeed been sent down to the operating room. Dr. E2, upon looking at the patient's chest, also commented that "this chest looks like Mr. A's." Given these responses, Dr. P did not pursue further confirmation measures. Dr. S, an expert in TEE, felt the dramatic drop in pulmonary artery pressure couldn't be explained by anesthesia alone but did not voice this strongly to the others.

Subsequently, Dr. F1, the lead surgeon for Patient A’s scheduled operation, entered the OR. He was informed of the TEE findings and viewed the monitor. Although he found the changes in findings from pre-op assessments to be unprecedented in his experience, he theorized that anesthesia or other factors might explain them and decided to proceed with the heart surgery on Patient B. Patient B, who had a relatively healthy heart, underwent an unnecessary open-heart surgery.

Parallel Error:

Simultaneously, in another operating room, Patient A (mistaken for Patient B) was being prepared for lung surgery. Dr. G, the anesthesiologist for Patient B's scheduled surgery, also failed to consciously confirm the patient's identity. Despite noticing a transdermal heart medication patch on Patient A’s back (which Patient A used, but Patient B did not) and discrepancies regarding a history of back surgery, Dr. G proceeded with anesthesia. Dr. H1, the surgeon for Patient B’s scheduled operation, also did not confirm the patient’s identity and commenced a thoracotomy on Patient A. During the surgery, Dr. H1 encountered unexpected findings, such as lung emphysema not seen on Patient B's pre-op scans, but continued, ultimately removing a benign cyst instead of the suspected tumor.

Systemic Failures:

Critically, the hospital lacked robust patient identification systems. There were no patient ID wristbands in use. Furthermore, there had been no specific pre-operative meeting among the surgical, anesthesia, and OR nursing teams to coordinate roles, patient entry times, or other logistical details for the concurrently scheduled surgeries.

Legal Trajectory: From Acquittal to Conviction

Several medical staff members involved in the mix-up, including Dr. P, Nurse C, Nurse D, Dr. F1 (surgeon for A's intended surgery), Dr. G (anesthesiologist for B's intended surgery), and Dr. H1 (surgeon for B's intended surgery), were charged with professional negligence causing injury.

- Trial Court (Yokohama District Court): Dr. P was acquitted. The court found that he had fulfilled his duty of care by taking certain measures after his doubts arose. Five other staff members were convicted and received fines or suspended sentences.

- High Court (Tokyo High Court): The High Court overturned the trial court's decision with respect to all defendants. It found that Dr. P had indeed breached his duty of care and that the measures he took were insufficient. His actions were considered in sentencing, and he was fined 250,000 yen. The fines for the other convicted staff were generally set at 500,000 yen.

Dr. P was the sole appellant to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (March 26, 2007)

The Supreme Court dismissed Dr. P's appeal, thereby upholding his conviction for professional negligence causing injury. The Court took the opportunity to articulate key principles regarding the duty of patient identification in medical settings.

Core Principle: Patient Identification as a Foundational Duty

The Court began by stating unequivocally that "in medical practice, confirming the identity of the patient who is the subject of the medical act is an absolute prerequisite for justifying said medical act." It described this as a "basic and elementary duty of care for medical personnel." While emphasizing that it is desirable for hospitals to establish organized, systemic measures for patient identification—including clear protocols, role divisions, and tools like ID wristbands—the Court noted these were lacking in the present case.

"Cumulative Responsibility" in the Absence of a System

Given the absence of a reliable hospital-wide identification system, the Supreme Court laid down a crucial principle:

"Medical personnel involved in surgery, such as doctors and nurses, are not permitted to trust that other personnel have performed the said confirmation and thereby judge that they themselves do not need to perform the said confirmation. Each person, according to their professional responsibility and role, has a cumulative duty (重畳的に - jōjōteki ni) to responsibly confirm the patient's identity."

This confirmation, the Court stated, must be performed, at the latest, before the commencement of any invasive procedure such as anesthesia. Furthermore, if circumstances arise after the initiation of anesthesia that cast doubt on the patient's identity, the medical procedure must be halted (unless at a stage where stopping is critically difficult or dangerous), and all relevant personnel must re-confirm the patient's identity.

Dr. P's Specific Failures

The Supreme Court found Dr. P negligent on two fronts:

- Pre-anesthesia Identification Failure: Dr. P's method of addressing the patient by surname ("Mr. A, good morning")—even if it was the hospital's customary practice—was deemed insufficient for confirming identity. The Court reasoned that patients awaiting surgery are often in states of extreme anxiety, tension, or may have impaired consciousness due to their medical condition or pre-medication. They might not notice being called by an incorrect name or might assume it was a slip of the tongue and not mention it. Therefore, Dr. P was negligent in not also confirming the patient's identity through other means, such as checking their appearance and other external physical characteristics against his prior knowledge of Patient A.

- Post-anesthesia Failure to Take Conclusive Confirmation Measures: After doubts about the patient's identity arose from observations of physical characteristics (teeth, hair) and an TEE findings, Dr. P did raise questions with other medical staff and took "certain limited measures for confirmation" (such as the phone call to the ward). However, the Supreme Court found these measures insufficient. Given that "substantial grounds for doubting the patient's identity had arisen," Dr. P was negligent in not taking "conclusive confirmation measures" (kakujitsu na kakunin sochi).

The Supreme Court acknowledged that other staff members did not take Dr. P's doubts seriously, making it difficult for him to ensure conclusive ID checks. It stated: "It can be assessed that Dr. P made a certain degree of effort to prevent the mix-up." However, it concluded: "Nevertheless, given that doubt based on considerable grounds had arisen concerning the most fundamental matter of patient identity, even if the above circumstances existed, it must be said that Dr. P did not fulfill his duty of care."

Discussion: Beyond Custom – The Standard of Care for Patient ID

The Supreme Court's explicit rejection of "hospital custom" as a sufficient standard for patient identification is a significant point. Simply following a routine or traditional practice (like a cursory verbal greeting) does not absolve medical personnel of their duty if that practice is objectively inadequate to ensure patient safety. This aligns with broader legal principles that medical standards of care are not solely determined by custom but also by what is reasonably required to prevent foreseeable harm, especially concerning fundamental safety checks.

The "Principle of Trust" and Systemic Safeguards

The "Principle of Trust" (shinrai no gensoku) in Japanese law can, in some circumstances, allow professionals working in a team to rely on their colleagues to perform their duties correctly. The Supreme Court's decision in this case implied that if a robust, reliable hospital-wide patient identification system and clearly defined roles had been in place, the application of this principle might have been considered differently. However, because such a system was absent, the Court imposed a cumulative duty on all team members.

This leaves open the question of how the "Principle of Trust" would apply if such systems were functioning. Some legal commentary suggests that even with advanced systems, certain core responsibilities, like a surgeon's final confirmation of patient identity before making an incision, might remain non-delegable. Others argue that a sufficiently reliable system could indeed allow team members to trust specific checks performed by others, thereby avoiding redundant efforts while maintaining safety. The High Court in this case had noted that "if the management system and role assignments were different, the specific duties of care owed by surgeons, anesthesiologists, etc., would naturally differ."

The Challenge of Junior Staff in Hierarchical Settings

Dr. P, an anesthesiologist with about five years of experience at the time, found himself in an undeniably challenging situation when his concerns about patient identity were not met with decisive action by more senior physicians, including attending surgeons and his own anesthesia colleague. The pressure to proceed in a hierarchical operating room environment is significant.

Despite acknowledging Dr. P’s efforts, the Supreme Court maintained that the absolute primacy of correct patient identification meant that his doubts, being substantial and well-founded, required conclusive resolution. The commentary around the case suggests that alternative, more assertive actions might have been possible, such as insisting that a ward nurse familiar with Patient A be brought to the operating room for definitive visual identification before proceeding further. The judgment also subtly highlights a potential imbalance, as some senior physicians who arguably played a role in dismissing or not adequately addressing the initial doubts faced different legal outcomes or were not prosecuted, a point of concern for fairness noted by legal commentators.

Broader Implications: A Catalyst for Change

High-profile medical errors like this patient mix-up often serve as catalysts for broader changes in medical safety practices and regulatory frameworks. This case, along with others around the same period in Japan, drew significant public attention and contributed to efforts to strengthen medical safety, including amendments to the Medical Service Act. Such incidents underscore the critical need for hospitals to invest in robust patient identification systems, implement clear team communication protocols, and foster a safety culture where all staff members, regardless of seniority, feel empowered to voice concerns and halt procedures if critical safety doubts, like patient identity, arise.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision in this patient mix-up case delivers a clear and firm message: patient identification is an inviolable and foundational duty in all medical interventions. In the absence of reliable, systemic hospital safeguards, this responsibility rests cumulatively on every member of the medical team. Each individual must actively confirm identity according to their role and position. While the "Principle of Trust" may have a role under conditions of robust systemic support, this ruling emphasizes that substantial and well-grounded doubts concerning patient identity must be definitively and conclusively resolved, even in challenging hierarchical environments, before a patient is subjected to irreversible medical procedures. The case serves as a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of basic identification failures and the high degree of vigilance required from all healthcare professionals.