A Broken Chain: Japan’s Supreme Court on Causation and Mistake in Criminal Instigation

Case: The Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Case No. 1949 (Re) 3030

Decision Date: July 11, 1950

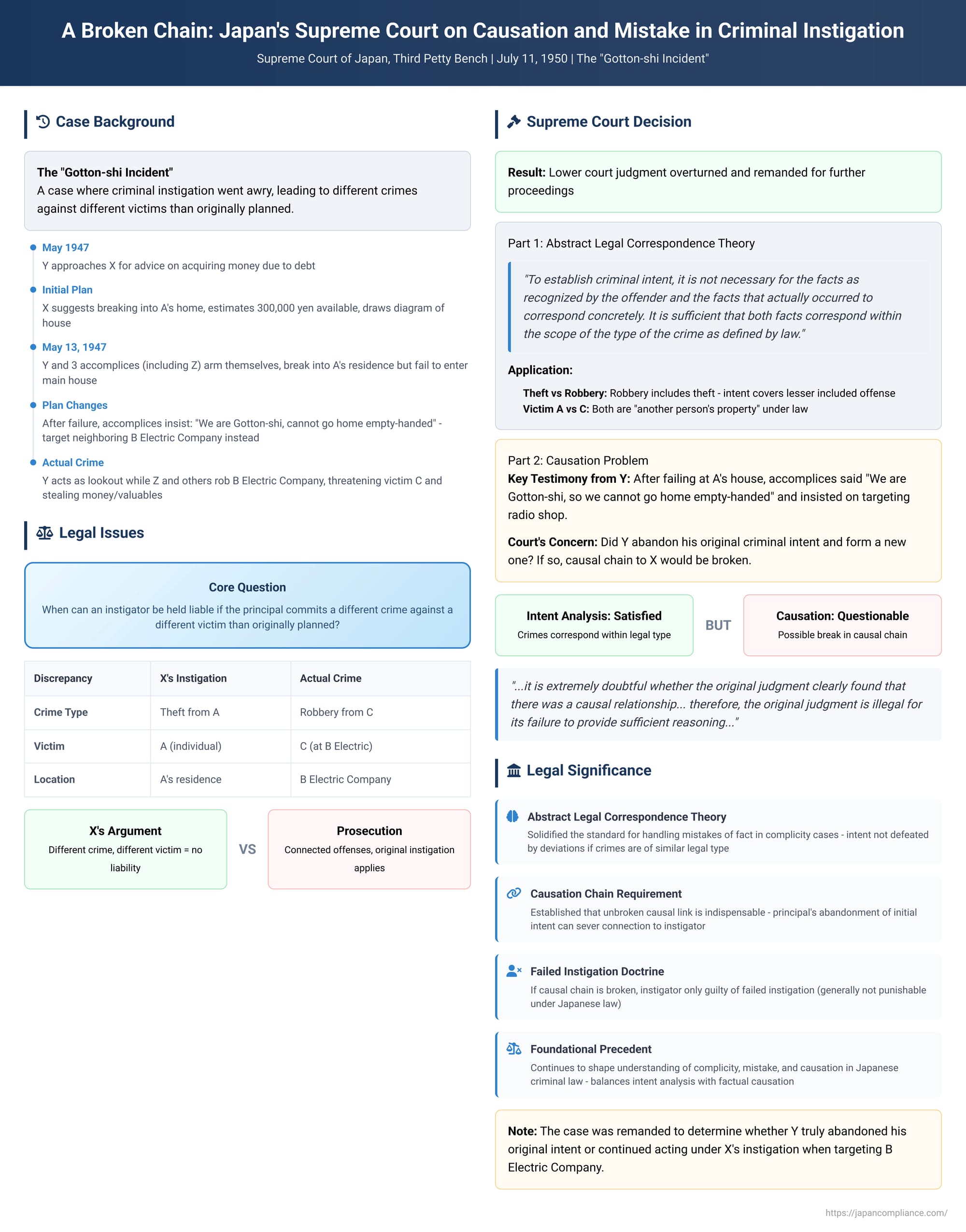

In a seminal 1950 ruling that continues to shape the understanding of complicity in Japanese criminal law, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed two fundamental questions that arise when a criminal plot goes awry. The case, famously known as the "Gotton-shi Incident" ("Gotton-shi" being slang for a professional burglar), forced the court to determine an instigator's liability when the person they incited commits a different, more serious crime against a different victim than originally planned. More critically, it explored the limits of causation, asking when a principal offender's new decision-making can sever the legal link to the original instigator.

Factual Background

The case originated from a conversation between X, the defendant, and Y. In May 1947, Y, facing significant debt and financial hardship, approached X for advice on how to acquire money. X, being familiar with the circumstances of a man named A, suggested that Y should break into A's home, estimating that A possessed around 300,000 yen. To facilitate the crime, X drew a diagram of A's house and the surrounding area.

Influenced by X's instigation, Y resolved to act. However, instead of simple theft, Y decided on robbery. On the night of May 13, Y, accompanied by three accomplices including Z, armed themselves with a katana, a dagger, ropes, and a crowbar. They proceeded to A's residence and successfully broke in through a locked back entrance. Once inside, however, they were unable to find a way into the main part of the house. Frustrated, they initially abandoned the attempt.

At this point, the plot took a decisive turn. Though their initial plan had failed, Y and his accomplices decided to continue their criminal endeavor. They conspired to break into the neighboring property, B Electric Company. Y acted as a lookout while Z and the other two accomplices entered the building. Inside, they threatened the sleeping occupant, C, and successfully stole money and valuables.

The lower court found X guilty of instigating residential intrusion and theft, viewing them as connected offenses. X appealed, arguing that he could not be liable. His reasoning was twofold: he had instigated a crime against A, which was never carried out, and he had never instigated any crime against B Electric Company. Therefore, he argued, he should not be guilty of instigating the crime that actually occurred.

The Supreme Court's Two-Part Analysis

The Supreme Court overturned the lower court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. However, its reasoning was nuanced. It rejected X's argument on the issue of criminal intent and mistake but agreed that the lower court had failed to properly establish the facts concerning causation. The judgment is best understood as a two-part analysis.

Part 1: The Doctrine of Mistake (Error) and Criminal Intent

The first issue the Court addressed was whether X could be held liable when the crime committed (robbery against C at B Electric Company) differed from the crime he instigated (theft against A). The Court established a principle that remains a cornerstone of Japanese law on criminal intent.

It ruled: "To establish criminal intent, it is not necessary for the facts as recognized by the offender and the facts that actually occurred to correspond concretely. It is sufficient that both facts correspond within the scope of the type (or pattern) of the crime as defined by law."

This is an articulation of the "Abstract Legal Correspondence Theory" (chūshōteki hōteiteki fugōsetsu). This theory holds that criminal intent is not negated by a mistake of fact, so long as the intended crime and the resulting crime share the same fundamental legal nature and protect the same core legal interests. The Court applied this principle to both discrepancies in X's case:

- Theft vs. Robbery: X instigated theft, but Y committed robbery. Robbery is essentially theft accomplished through violence or threats. The crimes share a substantial overlap in their core elements: the violation of another's possession of property. Under the Abstract Legal Correspondence Theory, since the intended crime (theft) is a lesser-included offense within the committed crime (robbery), the instigator's intent is valid up to the scope of the lesser crime. Therefore, the Court held that if causation were proven, X could be held liable for instigating theft.

- Victim A vs. Victim C: X instructed Y to steal from A, but the actual victim was C. The Court found this difference to be immaterial to the question of intent. The crime of theft requires the taking of "another person's" property. Both A's property and C's property fall under the legal category of "another person's property." As long as the offender intends to steal from someone, a mistake as to the specific identity of that person does not invalidate the general intent to commit the crime.

Thus, the Court concluded that X's legal argument on the grounds of mistake was incorrect. In principle, he could be held responsible for instigating the theft from B Electric Company, despite the changes in the crime's details.

Part 2: The Crucial Element of Causation

While the Court established that X's intent could cover the committed crime, it found a potentially fatal flaw in the prosecution's case on the issue of causation. For an instigator to be liable, their act of instigation must have a direct causal link to the principal's execution of the crime. The Court questioned whether such a link existed in this case.

The Court pointed to key testimony from Y, which suggested a break in the causal chain: "[Y stated that] after they failed to enter the main house of A, they gave up and started to leave, but the other three men said, 'We are Gotton-shi, so we cannot go home empty-handed,' and insisted on entering the neighboring radio shop, so Y waited outside."

Based on this testimony, the Court reasoned that it was highly possible that Y had abandoned the criminal intent that was formed as a result of X's instigation. The decision to rob B Electric Company may not have been a continuation of the original plan but a new criminal resolution, motivated by the strong insistence of Y's accomplices.

The Court explained that if Y had truly abandoned his initial intent and formed a new one, then X's act of instigation did not cause the final crime. The legal chain of causation would be broken. In such a scenario, X would only be guilty of a "failed instigation" (kyōsa no misui). Under Japanese law, failed instigation is generally not a punishable offense. An instigator is only punished if the principal at least attempts to commit the instigated crime. Since Y never even reached the stage of attempting a theft from A, X would escape liability entirely if the causal chain was proven to be broken.

The Final Decision and Legacy

The Supreme Court did not acquit X. Instead, it found that the lower court's judgment was flawed because it had convicted X without clearly establishing the crucial fact of whether the causal link between X's instigation and Y's crime remained intact. The verdict stated: "...it is extremely doubtful whether the original judgment clearly found that there was a causal relationship... therefore, the original judgment is illegal for its failure to provide sufficient reasoning..." The case was sent back to the High Court for a new hearing to determine this factual issue.

The "Gotton-shi Incident" remains a landmark case for two primary reasons:

- It solidified the Abstract Legal Correspondence Theory as the prevailing standard for handling mistakes of fact in cases of complicity. It clarified that an instigator's liability is not defeated by deviations in the execution of a crime, as long as the intended and actual offenses are of a similar legal type.

- It powerfully underscored that a clear and unbroken chain of causation is an indispensable element for establishing an instigator's liability. It established that a principal offender's abandonment of their initial criminal intent and the formation of a new, independent resolution can sever the link to the original instigator, thereby absolving the instigator of guilt for the final act.